The vast majority of people involved in Steampunk are interested in history but, like with science, there's something about history that we don't talk about very often:

The holes.

That is, the gaps in our knowledge, not physical holes like that pictured above. That's a real hole, by the way, not Photoshopped.

Donald Rumsfeld, the former US Secretary of Defense, did a great job of summarizing epistemology in the following quote:

"There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know."

Epistemology, for those who don't know, is the study of knowledge itself. While many of us take the known knowns for granted, preferring to study the known unknowns, perhaps we shouldn't take the known knowns at face value.

Confused? Good.

While the majority of us studied history in school, your teacher probably never spent any time talking about exactly why we know the things we know, and how certain we are of them.

Before the advent of (relatively) impartial recording mediums like audio and video recordings, things needed to be written down by a human. This means that every part of our knowledge of pre-20th century history (minus the knowledge gleaned from the study of physical artifacts) has been filtered through a human perspective.

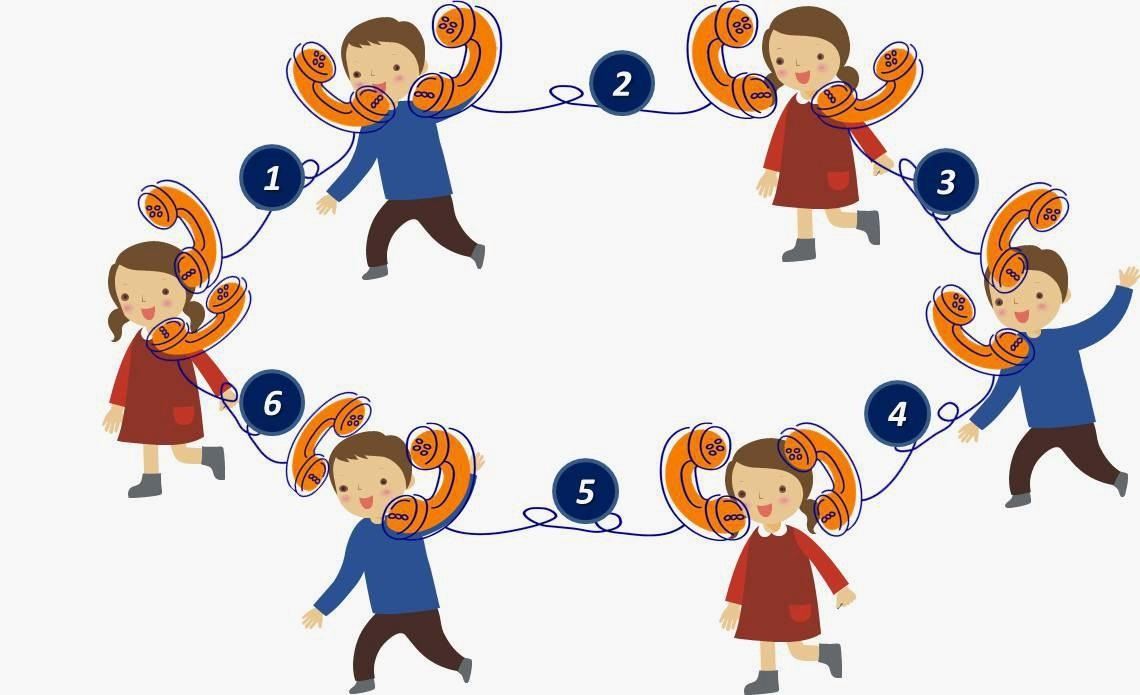

That doesn't sound so bad, right? Before passing judgment, stop and consider that many of the major events in history were written down by people who hadn't witnessed them firsthand. Then remember what happens when you play a game of Telephone.

And what about the people who wrote things down after personally witnessing them? That's fine, right? You may think so, but I direct you to the modern realization that eyewitness testimony is extremely unreliable, and may soon be disallowed in court.

If every piece of written history is unreliable, does that mean that our whole understanding of history is wrong?

Well, no. In fact, there's an entire field of study that you've probably never heard of that's dedicated to this very problem. It's called historiography, and it's about investigating the sources of our knowledge of history, rather than the history itself. They do things like verify events from multiple accounts, and try to discover the truth from a medley of conflicting recollections. They also document multiple interpretations of events, try to isolate recorder biases, and just generally do the sorts of very important things that you'd think more people would know about.

As a result of that work, most of the things we learn in school are things we're pretty sure about, with something like 99% certainty. The big events are much easier to verify through multiple sources than small events, which is why you hear a lot about, say, George Washington, but not much about Joe Soldier who fought in the Revolutionary War. Joe Soldier may have written about himself, but chances are good that no one else wrote about him, so what we end up with is a fundamentally biased piece of historical evidence that can't be backed up by external sources.

So despite history and historiography's best efforts, there's only so much that can be done with limited information. After all, the past is gone. We can't just pop back a hundred years and ask questions. If someone didn't think to record something in some way, it's gone. When you go back a long way in time, you start to lose really substantial things that no one recorded, like music, martial arts, oral traditions, and more. Those things are just gone, and there's no getting them back.

No matter how much we think we know about Roman swordplay, for example, it's all just extrapolation. History professor Matthew Giddings once asked me, "What [music] did Caesar listen to? Ramses? Sargon of Akkad? We'll never know for sure, because it never got written down. So, our knowledge of the past is linked in a very fundamental way to the preservation of stuff."

Well, sure, Roman Empire music is literally ancient history. It's no real surprise that we don't know things that happened thousands of years ago, right? Surely we have a nearly perfect understanding of the last few centuries.

Yes and no.

As compared to bronze age history, it's like the difference between night and day. Nearly every aspect of 19th century life was written about by someone, as a result of literacy becoming more and more prevalent among all classes and walks of life. And yet note that I said "nearly every aspect". We tend to gloss right over this part because Hollywood films make it seem as though we know every single detail of the 19th century, but that simply isn't true.

Unfortunately, most of those things are unknown unknowns, to return to the quote from the beginning of the article. That is, we don't know that we don't know them.

For example, my niche is literature, so I can say with certainty that we've lost a large number of pulp fiction that was common in 19th century England and America. Exactly how many stories we've lost, though, we have no idea. Sometimes we'll find accounts in which someone will talk about a book or story, cluing us in to its existence, but without that, we have nothing. The problem is twofold: on one hand, those books were pulpy, so it wasn't seen as something worth preserving. On the other hand, they were literally pulpy, made from low-quality wood pulp which has since degraded significantly.

Take a moment to consider the relationship between historical knowledge and the preservation of information.

Now think about the nature of electronic communication, and consider that hardly anyone owns record players, VCRs, cassette players, and floppy disk drives anymore. Not only that, but entire hard drives of digital information can be annihilated in a single strong pulse of electromagnetism. It's scary to think that someday hardly any records of this period of history will remain. Things are no longer built to last.

So next time you're attending a class or a panel on history, remember exactly how shaky a foundation our understanding of history is built upon, and ask yourself (or your teacher) how we know the things we know, and whether the person who recorded the information had a personal agenda. It may give you a whole new understanding of history!

Images from Guatemalan Government, Georgia Regents University, CreateMeme, Lexician, Classic CMP

Just updated your iPhone? You'll find new emoji, enhanced security, podcast transcripts, Apple Cash virtual numbers, and other useful features. There are even new additions hidden within Safari. Find out what's new and changed on your iPhone with the iOS 17.4 update.

5 Comments

You, Sir, are an extrordinary gentleman! Everything you write has made me pause and think. I bow before a master.

I have always loved history and have wondered about that which was not written. Your comments about the digital age should be heeded by one and all.

Aww, thank you, Lisa!

I'm just glad that people seem to enjoy my articles. =)

Hi Austin, interesting article. You mention that some things recorded by a single source may have been done so with an agenda. To extend the phrase, would you also agree that it is likely that record keepers in an international conflict tend to bias information according to their own country's views (in short propaganda) and that the conflict winners' side is usually accepted as the right one and down the track as history?

Oh, sure, Kurt. The phrase "history is written by the victors" didn't come about for no reason.

That said, there are two different types of history. The history that people who study history know, and the history that everyone else knows.

For example, in the United States, there's a board of education in Texas that has an undue influence on what information is included in American school textbooks. As a result, the vast majority of the American public is exposed to history that has been filtered through a single advisory committee.

Despite that, there are thousands, if not millions, of books written about history that are not filtered through that committee, which provide a different, more nuanced, view of history. Any average citizen could buy one of those books are read it in order to expand their knowledge, but most of them don't care, and can't be bothered.

I suspect that that will always be the case, that there will be an "accepted" version of events for the populace at large, and that more information will be available for those who look for it.

North Korea is an excellent modern-day example. Information is tightly-controlled inside Pyongyang, but outside information still gets in. Destroying all record of something is a really difficult thing to do, and it gets exponentially more difficult the bigger the impact that thing had on people.

Austin,

Thank you for that amazing piece. I really enjoyed reading it. Sure I'd thought vaguely about that type of thing, but never like you just explained. I was wondering what I should do now. I have to do a history project but I didn't want to do a project that has been over done. I wanted to find some exclusive, not well known story, but now I see that wouldn't be the wisest decision, considering there wont be as many facts to back up the project! Do you have any suggestions? I understand if you don't want to give me some pointers, I just want to have a really good project and I was wondering what was the best way to go about doing it.

Thank you!

-Maddie

Share Your Thoughts